CHARTS THAT DON'T CHANGE

Harry Guild & Dean Matthewson

20/10/2021

Marketers would have you believe that consumer beliefs and behaviours are constantly changing. ‘This new generation is different.’ ‘This is a new normal.’ ‘Yoghurt buyers will never be the same again.’ But is that really true? To find out, BBH Labs analysed how Britain’s attitudes have changed over the past 20 years. The results, write Harry Guild and Dean Matthewson, tell a different story.

Things have changed

I once heard a client observe that agencies only ever use two types of charts: those that go up and those that go down.

It was a throwaway line. The sort of mid-tier joke that greases the wheel of any working relationship. Everyone laughed politely, before returning to the dramatic-looking chart on the screen.

But there was a truth in it.

When was the last time you saw a flat line graph in a pitch deck?

As a rule, our charts either look like this.

Or like this.

(And sometimes like this - if it’s an awards entry).

Time and again, we cherry-pick the most dramatic charts and statistics possible.

Time and again, we scream things have changed.

An interest in change is no bad thing. There can be great rewards from catching a trend before others have cottoned onto it: in a favourable market context, the first mover enjoys outsize advantages over slower competitors.

But our industry is not merely interested in change. It is obsessed with it.

Change is to marketers what lightbulbs are to moths. We fixate upon emerging behaviours, fetishise the latest platforms, and fantasise about ‘new normals’. The world as understood through agency decks is a place of constant upheaval.

There is a simple reason for this obsession. Change sells.

What are we saying to clients when we present these charts? We’re saying act now. We’re saying ‘Don’t miss the boat’, ‘Abandon ship’, ‘Buy what we’re selling’.

This is part of the problem with the modern agency landscape. Our process has become geared towards the selling of ideas, rather than the value of the ideas themselves. Symptoms of this problem crop up everywhere (the number of hours put into deck fiddling, the unblinking use of questionable data sources to fit a narrative) but perhaps nowhere more so than our fixation with dramatic looking charts.

As a result, we’re ignoring the dullest, yet often most useful, data: the numbers that haven’t moved in decades.

Flat charts don’t sell. They instil no urgency. But they are bankers. They indicate an unchanging truth about the consumer or market. And that is something you can build a brand upon.

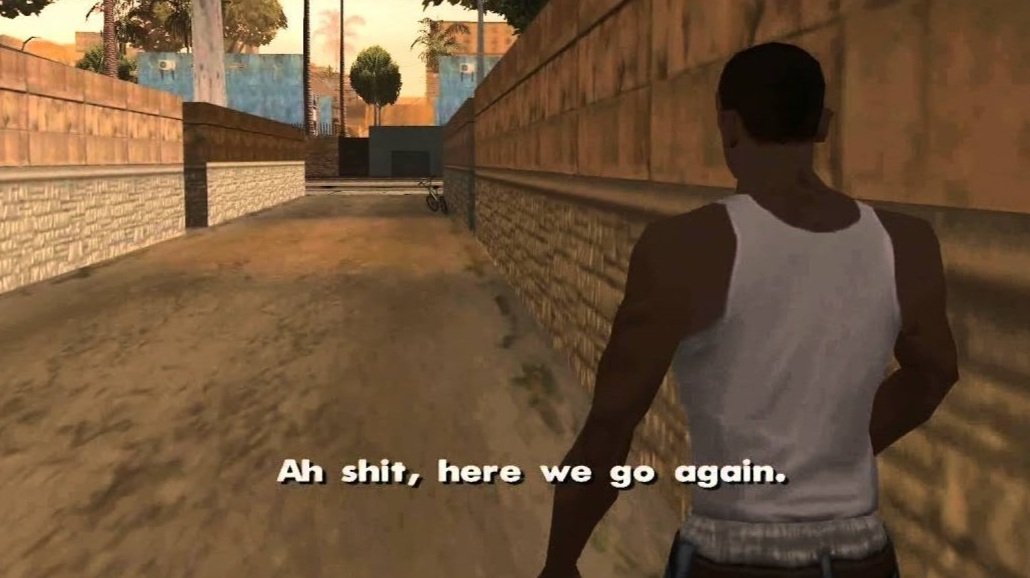

Bill’s point is proven by the continued popularity of this pose among male CDs

What are these great unchanging truths?

To find out, we turned to TGI.

Every year, TGI asks the British public for their stance on several hundred statements. These statements range from the political (“after retirement, finances are your own responsibility”) to the personal (“I am constantly trying to lose weight”) to the philosophical (“You can judge a person by the car they drive”). By measuring how the public’s opinion on these issues changed over time, we hoped to understand whether Bernbach’s ‘unchanging man’ idea actually held water.

TGI’s survey data spans from 2000 to 2020. That’s a period containing 9/11 and the War on Terror, Obama, the worst recession since the Great Depression, the Arab Spring, #MeToo, Trump, Brexit, BLM, COVID, the rise of the digital world. To give you a sense of just how much changed during the course of these surveys, here’s a Daily Mail article from December 2000.

Were these seismic changes to the outside world reflected in consumers’ attitudes?

In a word: no.

Over the course of twenty years:

45% of topics saw opinion change by fewer than 5 percentage points.

74% of topics saw opinion change by fewer than 10 percentage points.

By focusing only on those elements that have changed dramatically, marketers are ignoring at least half, if not three-quarters, of all consumer information. For an industry drowning in data, we remain remarkably poor at using it.

Hopefully the following will help correct this oversight. Prepare yourself for some of the least dramatic charts you will ever see published by an advertising agency.

Charts that don’t change

For starters, people are just as scared of the future as they used to be.

They still believe themselves to be loyal to brands (although this does waver following the financial crash).

Debt is an eternal human fear.

Despite terrorism and COVID driving two decades of increased government intervention, people’s receptiveness towards authority is the same now as it was in 2000.

People still love their families, and still prioritise them above all else.

People still hate mess. And wrinkles.

Our love of gardens is evergreen.

And the same is true of restaurants.

These might not be the most exciting charts in the world, but they’re the fundamentals. They’re our consumers’ unchanging constants. As marketers, we should know this data inside-out.

Unchanging charts can also teach us something about persuasion. Take attitudes towards gender, for instance.

Given that our analysis begins at the height of Lad Culture and ends in the wake of Me Too, it seems reasonable to expect a great deal of change in views about women.

And yet, agreement that ‘a woman’s place is in the home’ has stayed constant over the past two decades.

Bleak as this looks, it is not the full story. Whilst agreement has remained constant, disagreement has actually increased by 10%.

It is not the cavemen who have been converted, but the fence-sitters.

A similar phenomenon occurred with the view that ‘real men don’t cry’: agreement remained constant, but neutrality declined.

This data hints at something intriguing. Should we even bother with the die-hards? Are some factions too far gone to ever be swayed? Is it not a better use of resources to focus on the swing states?

Whatever the answer, this is a question that never would arisen had we adopted the traditional agency approach. Had we only been on the lookout for dramatic charts, we would have only cared about the +10% shift in disagreement, and overlooked all this vital nuance.

Charts that do change

So, what has changed over the past twenty years?

It’s clear that our financial views have been lastingly shaped by the Great Recession.

And tightening financial circumstances change our priorities.

Our shift away from the physical world to the digital one has impacted our relationship to cash and newspapers.

Only one topic has seen large shifts in both directions during this period, and that is cannabis legalisation. The reasons for this are hazy.

Which topic has seen the largest shift since 2000? Over the course of these two momentous, tumultuous decades, on what issue has public opinion changed the most?

Terrorism? Online dating? Veganism?

If only.

What next?

To recap.

In the main, consumer attitudes have changed very little over the past 20 years. But our industry uses the threat and/or opportunity of sudden change as a sales device. This has led to a widespread cherry-picking of only the most sensationalist pieces of data, chasing the fads rather than the fundamentals.

Which might go some way to explaining why TV ads are now twice as annoying as they were in 2000.

So, how do we fix this?

We need to stop idolising change, and instead see the value in unchanging data, in Bernbach’s ‘unchanging man’.

We need to stop viewing consumer behaviour only in a short term window, and instead take a longer view, separating the fad from the fundamental.

And finally, we need to start showing clients a different kind of chart. One that doesn’t go up or down.

It’s simple, really. We just need to change.