WHODUNNIT? FIVE SLEUTHING SKILLS FOR STRATEGISTS

JOY MOLAN

21/03/2023

Joy Molan, Senior Strategist with BBH London, explains why murder mystery detectives are basically advertising strategists with better neckties and catchphrases.

During the Christmas holidays, 35 million people - including me - decided to unwind by watching a gruesome murder with their loved ones (AKA Knives Out: Glass Onion). The movie makes for compelling viewing and inspired plenty of further content (including the official real-life Glass Onion murder mystery game created by BBH).

Glass Onion fuses Hitchcock-esque suspense with the century old rules of the ‘fairplay whodunit’ genre, with blockbuster success. Like all murder mysteries, the viewer is compelled by the detective’s drive to uncover the culprit. Detective Benoit Blanc miraculously creates order from chaos to deduce what kind of game is afoot.

So how does he do it? And why is this relevant to advertising strategy?

Murder mystery detectives like Benoit Blanc don’t possess superpowers. They don’t have some extraordinary, innate gift that makes them better at solving mysteries than the rest of us. Blanc confesses, “I want to be clear. I am not Batman. I can find you the truth, I can gather evidence, I can present it, but that is where my jurisdiction ends”.

The reason for this can be traced back to the 1930s, when the British Detection Club was founded. The club’s members, including Agatha Christie, formalised the ‘fairplay whodunit’ genre with an oath which forbade members from employing magical happenings, acts of god and any unnatural fixes in the solving of their crimes. Therefore, the big reveal (which characterises the genre) is simply the result of rational deduction.

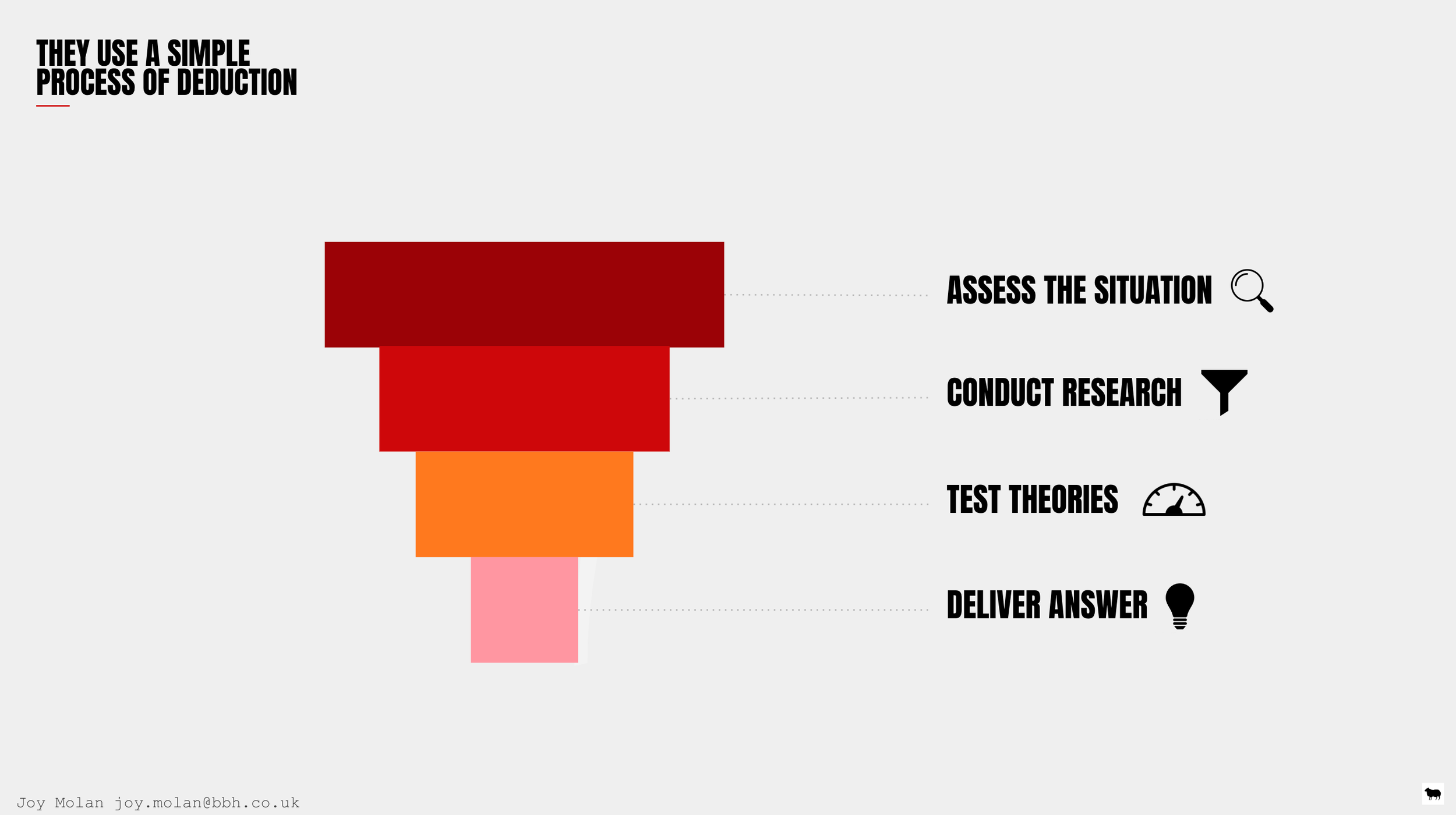

A detective shows up at a country manor, glamorous train, yacht or picturesque village. They sort through the bumsteers, local gossip, clues, and eventually deduce the truth. They audit the situation, leverage well-known psychological principles, test their theories and – finally – deliver their conclusion in a suspenseful moment.

Much like a first strategic presentation, pitch meeting or creative briefing.

Here we reach the nub of it. I think murder mystery detectives are advertising strategists with better neckties and catchphrases. Change the title of the above chart to ‘strategic framework’ and it could easily be repurposed to explain how we might arrive at a creative proposition.

From analysing a number of methods employed in the canon of ‘fairplay whodunits’, thrillers and relevant examples related to the field of criminology, here are five rules of sleuthing for strategists that we can apply to our work. Because once the game is afoot, there are rules to follow.

1 - Be inquisitive

This might sound obvious, but is surprisingly overlooked by characters in murder mysteries and, I’d argue, in real life.

Let’s start with an example from Christie’s Miss Marple story The Body in the Library (warning: spoilers).

Miss Marple is often described by people as a “busybody” because of her habit of showing up in new places and doing a better job than the police. She makes it her business to know the situation and suspects better than anyone. Much like a good Strategist might show up at research focus groups, rather than wait on second hand reports from clients or research agencies. They might visit a factory where the product is made or the store where the products are sold.

Miss Marple makes a point of being there in person. In The Body in the Library, she shows up in a tiny village after a shocked Colonel Arthur Bantry contacts her to investigate the mystery of an unknown woman, whose body has been found in his library. The police are called, but soon hit a brick wall. They seem to think the victim is a missing dancer from a coastal town that the Bantrys didn’t even know. So, how did her body end up in the library?

Because Miss Marple is there on the scene, she notices that the victim has recently dyed platinum blonde hair, bitten down fingernails and her dress is cheaper than you might expect of a famous dancer. This isn’t in keeping with the supposed victim. From talking with those related to the family and suspects, Marple deduces that the victim is in fact a local Girl Guide, also reported missing. She has been dressed up to appear to look like the dancer in what transpires to be a botched attempt to steal the dancer’s fortune. The Girl Guide was sadly in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Miss Marple has no secret tool the police don’t, but she’s better at observing and gathering insights.

While our own work is hardly life or death, we can see the impact that proper insight hunting has on advertising campaigns. One method touted in Planning training workshops is: take an observation about customer behaviour or attitudes and ask “why?” around seven times to uncover the real insight behind it. Take the Planning team on ‘This Girl Can’ who dug deeper into the reasons why women exercised less than men (see the case study verbatims below), and unearthed all sorts of complex emotional and physical barriers, resulting in one of the most powerful campaigns of recent years.

Or the story of John Hegarty and Barbara Noakes visiting the Audi factory and spotting a faded poster on the wall with the words 'Vorsprung durch Technik’. Three words that could easily have been overlooked, but which came to define the Audi brand.

What happens if we’re not inquisitive? Thomas Gwin, Head of BBH Effectiveness, warns against the insight ‘wind tunnel’ to which our industry often falls victim. The result is a sea of sameness across categories as brands use the same cultural reports as the basis of their brand and campaign strategies.

So, what might we find if we go beyond the obvious insight? What if we went and spoke to more customers first hand? What if we met people face to face like in the This Girl Can research, not just on Zoom calls or hidden behind two way mirrors?

2 - Remember forgetfulness

Please excuse the oxymoron. What I mean is that people - whether murder suspects, witnesses or customers - are highly fallible. That’s because we’re all driven by subconscious emotional shortcuts and memories, as evidenced in the works of Daniel Kahneman, Les Binet and Peter Field, and System 1’s Orlando Wood, to name a few. But it’s also clear in every Strategist’s first-hand experiences of audiences misattributing ads, saying they always do one thing in research (then doing the opposite in real life), or saying they buy a brand for a rational reason when it’s really because it reminds them of their childhood or because of a catchy jingle.

The murder mystery detective works with this not against it.

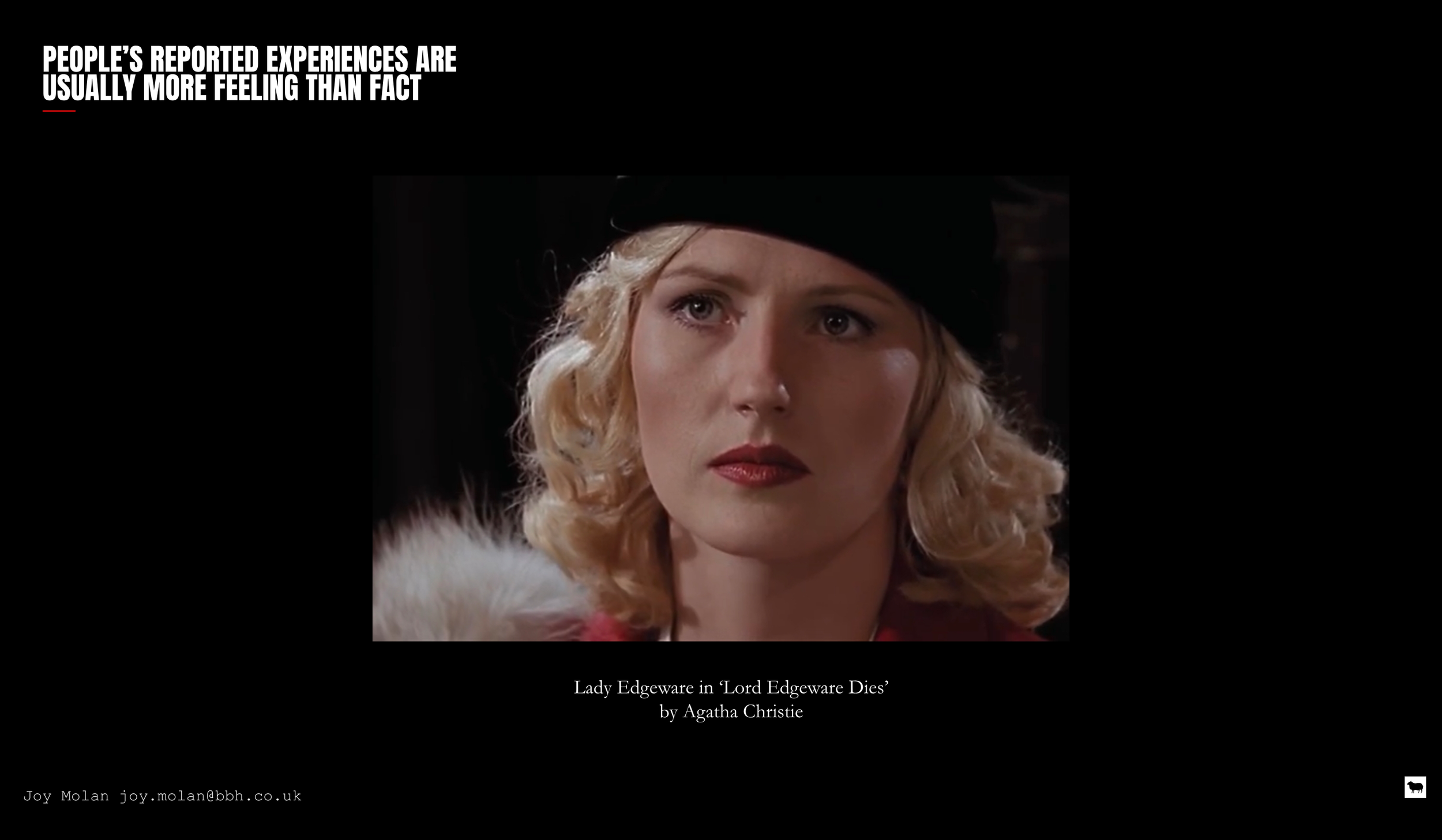

In Christie’s Lord Edgware Dies, Poirot is told that the prime suspect - Lady Edgware - was seen in the house on the night of the murder. She was seen crossing the hall by a servant from the upper floor landing, shortly after the murder. Yet a society columnist also reports having seen Lady Edgware that night at a party on the other side of town. How can one woman be in two places at the exact same time?

The truth is that both parties think they saw Lady Edgware because that’s whom they expected to see. The servant, from a distance, saw the blonde hair, the distinctive clothing (her distinctive assets, if you will). The society columnist knew the Lady was invited to this party, so when a woman who looked like her arrives, they assumed it’s her. Both are using System 1 thinking, not System 2. Emotional shortcuts, not rational analysis. Poirot knows to question what they say they saw because he knows everyone is fallible and it’s much easier not to use our little grey cells. (It turns out one is an imposter, the other is real. But I won’t ruin it by saying which is which.)

Even real-life criminal law students are taught to be wary of this fallacy. In the 1980s, an experiment was carried out on first year law students. A professor turns up flustered to the lecture hall and launches into a lecture on geology. The law students begin awkwardly giggling because this man is obviously lost. They wonder if anyone’s going to say something. After about ten minutes, the right lecturer shows up and tells him he’s got the wrong room. What a relief - panic over. Except the lecturer then turns to the class and asks them to write down a description of the man they just saw. They’re asked to read aloud their descriptions, which are all wildly different. Some have him with a beard, others clean shaven. Glasses, no glasses. The lecturer says, “You had ten minutes in good lighting and focused attention. Now consider what it’s like for witnesses in the real world.” So they learn to expect fallibility.

So what can this teach us as advertising strategists?

If we have 30 seconds to make a memorable impression, it’s rare. 60 seconds is a luxury. Usually, it’s only six on social media. That’s why we have to use “fame, feeling and fluency” - the equation popularised by System 1 - to our advantage. We must exploit a brand’s distinctive assets, generate emotion, and do it loudly or noticeably (like Lady Edgeware crossing the hall). One of the early iconic examples of “fame, feeling and fluency” is David Ogilvy’s Hathaway man; a distinctive character with a backstory and a striking eye patch, who sold shirts like nobody’s business. Maybe the law students would have better remembered the geology lecturer had he been wearing an eye patch?

3 - Define opportunities and motives

Cluedo plays to our fascination with the ‘fairplay whodunit’ genre. It was also employed by the characters of Knives Out: Glass Onion to deduce the culprit.

A typical deduction process in Cluedo might look like the below (note: motives don’t run too deep in Cluedo).

But what if you retitled those columns? Look familiar?

And what if we repurposed it for a famous campaign, like this Marmite one?

Ultimately, the detective has to look for opportunities for someone to do something (physical availability - were they in a place where they could take a certain action or receive a certain message?). And did they have a motive? This is exactly what we, as Strategists, need for our comms to be effective. Can your customer find your brand of dog food in aisle three? Will they be reached by your TV advertising or do they only watch Netflix?

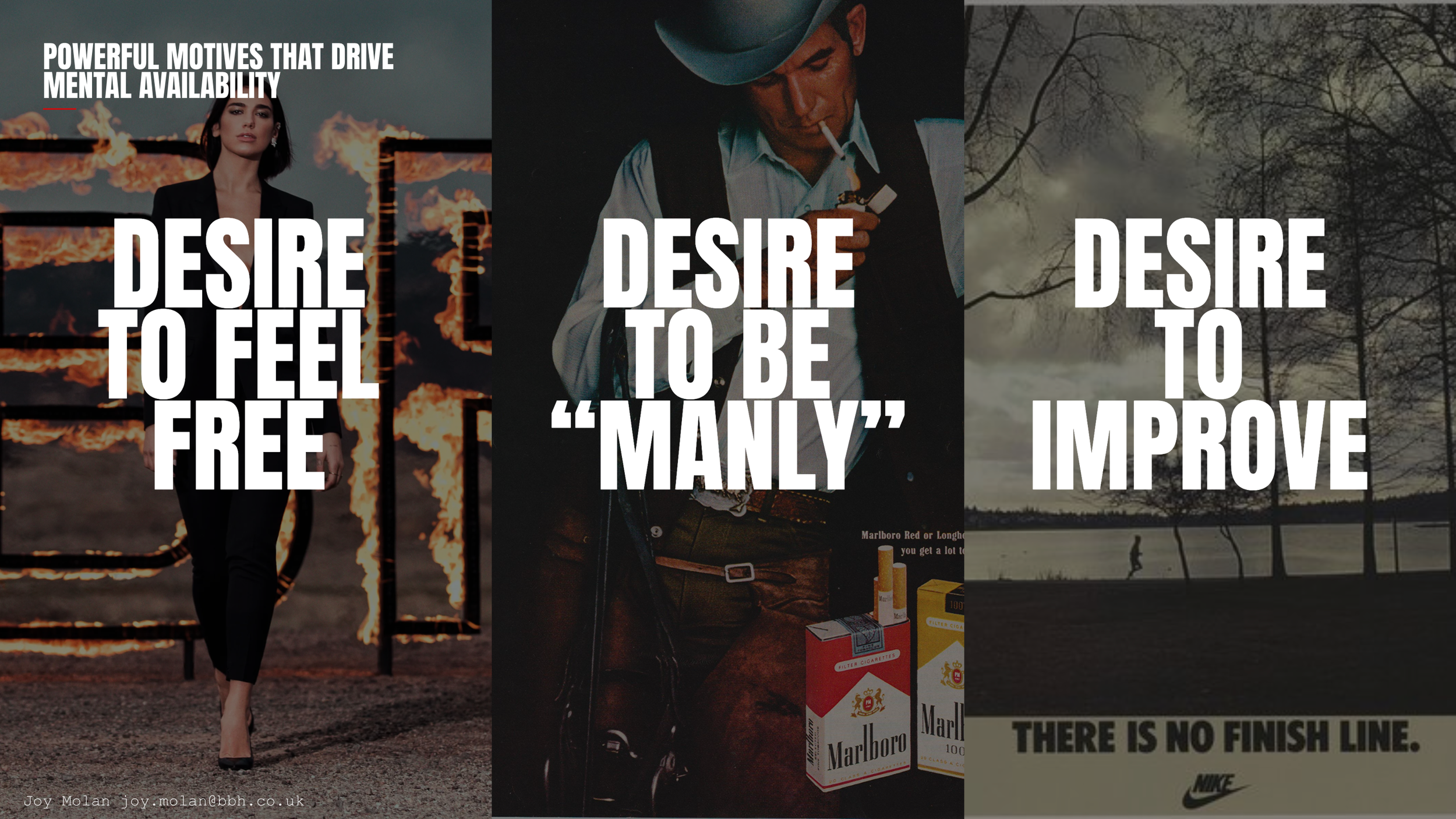

Then, have you created sufficient mental availability for your brand, product or service? Distinctive assets (like jingles, characters and catchphrases) help, but this also relies on generating deep emotional connections. You can see some famous examples here, from YSL perfumes to Malboro to Nike.

As Hegarty says, “information goes in through the heart”. So, what’s your audience’s motive? How will you ensure physical and mental availability?

4 - Play with priming

A detective knows that sometimes nudging is more powerful than telling. They are masters of behavioural psychology.

In An Inspector Calls by J.B. Priestly, an inspector shows up at a well to do family home and suggests all members of the family are implicated in the death of a young woman. The family is terrified they all might have inadvertently been involved in killing this girl. But only when the inspector is about to leave do they start to question things. How do they know he is a real detective? Because he said he was. How do we know the woman is dead? Because he said so. How do they know he all individually showed them a photograph of the same woman, not many? Because he said so. Have they actually confessed to multiple murders, not just one? Who knows…

If we look at the application of priming in marketing, the examples are just as powerful. In an experiment in 1999, a supermarket played French music in store and saw sales of French wine exceed German. The supermarket then switched the music out for German, and German wine outsold French.

Or how about the pop up, where Greggs had a stand at a farmers market and changed its name to ‘Gregory & Gregory’ - and unwitting middle class foodies rated it as delicious.

Advertising’s OG mad man bad boy, the late George Lois - the man behind those amazing Times Square Tommy Hilfiger ads and the iconic Andy Warhol Campbells soup Esquire cover - famously said:

What subtle priming can we do through the overall customer experience to make comms work harder?

5: Finally…zag to find the answer

BBH’s agency belief is the power of difference. So, as Strategists, we’re all versed in the benefits of “zagging” while the world zigs. Similarly, a great detective always zags to find the answer.

One of the rules followed by the Detection Club is that the culprit can never be too easy or obvious. This is referred to as NOS (never the obvious suspect). Chiefly, the murderer cannot be revealed to be the servant, who has easy access to the whole house and doesn’t act as a central character in the drama.

NOS sounds awfully familiar. Because it could also be said like…

It goes without saying that adopting this mentality as a Strategist can lead to category redefining work. So, let’s always ask ourselves: is there a less obvious answer?

In summary:

I hope these five sleuthing rules for Strategists come in handy with any future briefs (or if you happen to find yourself at a remote country house with murderous residents).